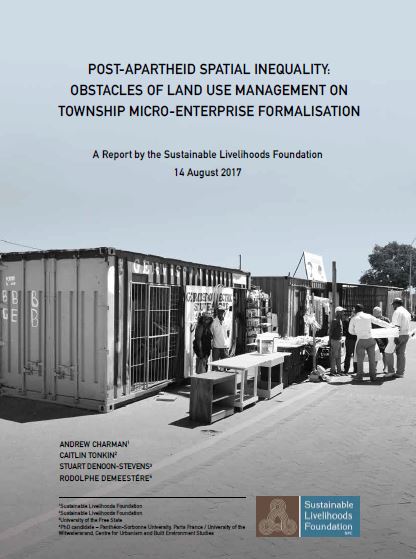

Post-Apartheid Spatial Inequality

Obstacles of Land Use Management on Township Micro-Enterprise Formalisation

Land use management centres on the notion of protecting people and the environment from the externalities of development. It is central to strategic planning to ensure the sustainable provision of public utilities, transport infrastructure, housing, and economic infrastructure. Land use management also provides an important legal/institutional framework to uphold property values and so safeguard the municipal tax base and investment. In South Africa, there is a complex web of legislation (which transverses the three tiers of government) through which the state aims to manage land, control building developments, and determine the places and forms in which people can conduct business and operate an enterprise. The Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA), 2013, clarifies the roles of government in land use management. SPLUMA is an important step towards redressing the apartheid legacy of spatial injustice: the Act introduces the four principals of spatial justice, spatial sustainability, spatial resilience, and efficient and good administration to guide land use governance.

The impact of South Africa’s spatially unjust land-use systems on poverty and inequality has been studied in broad (conceptual) terms. Yet the picture of how urban land-use systems are actually managed and how they impact on entrepreneurship has been under-researched. This report aims to address this knowledge gap. We specifically focus on the way urban land use management systems have impacted on (informal) micro-enterprises in the township context. This impact stunts the process of formalisation and/or the growth in business activity. Our point of departure is the argument that enterprise formalisation should be regarded as a strategic objective of economic development in the township economy. As in land use management, formalisation enables the state to regulate business practices (to permit new entrants and competition), ensure adherence to social standards, secure tax revenue, curtail the production and distribution of illegal goods, and increase the opportunities for enterprise growth through investment.

The report will illustrate the ways in which land-use management systems have intentionally (as well as unintentionally) reinforced apartheid-era town planning and spatial injustice in the township instead of nurturing economic growth. The report shows how compliance with land management systems is near to impossible for micro-enterprises. For these entrepreneurs, the land-related processes which people have to navigate to obtain business compliance resemble a Kafkaesque world: one in which the rules are nightmarishly complex, incomprehensible and illogical. Partially as a result of these challenges, the great majority of township informal microenterprises do not comply with land management system requirements and gain few or no benefits. They have no alternative to trading illegally. We refer to this process as ‘enforced informalisation’. The report details evidence of the implications of ‘enforced informalisation’ on house taverns, house shops, early childhood development (ECD) centres, and street-based container businesses. Furthermore, the report explains why most township micro-enterprises do not adhere to the land use management system in terms of:

- Zoning rights or consent use rights;

- The proportion of floor space utilised by business activities;

- The absence of a separation between business and residential activities;

- The absence of approved building plans;

- The failure to adhere to municipal by-laws relating to environmental health, food safety and the use of business signage; and

- The failure to adhere to informal trading by-laws and restrictions on trading activities within roads.

The report concludes that the objectives of spatial justice and spatial resilience have little advanced since 1994. This result can be attributed to the combination of inappropriate policy framing, non-supportive legislation (especially at the municipal level), the absence of political will to foster township economic growth and formalisation, and the persistence of apartheid-era concerns with maintaining control to prevent ‘unruly’ social and economic activities. Based on detailed evidence, the report amplifies the argument that South Africa requires a land-use system that can more effectively operationalise the principles of spatial justice and spatial resilience, whilst making allowance for the economic marginalisation of township communities. Such a land system needs to recognise the fluidity of urban conditions and the multiple uses of land for business, social, cultural and residential purposes.

Abstract based directly on the original source

Comments